Published on Feb. 9, 2023

The breeding perspective on the current crisis in the egg sector, by Nick Bailey

Two crucial decisions underpinned the effectiveness of the Hendrix Genetics breeding programme.

From a genetics perspective, in just 6o years, layer breeding companies have achieved incredible progress. Genetic excellence and technology advances have resulted in greater sustainability and efficiency gains than those achieved in many agricultural sectors. The outcome is modern hybrids with performance and persistency characteristics that would have astonished the poultry pioneers of the first half of the 20th century. Focussing on the end of the laying cycle has produced birds that are naturally healthier for longer, and capable of laying high numbers of first egg quality eggs later into lay, extending the productive life of layers.

Two crucial decisions underpinned the effectiveness of the Hendrix Genetics breeding programme – the extension of the pure line testing programme, first from 60 to 80 weeks in 2000 and then to 100 weeks in 2008. This was necessary because decades of selective breeding had reduced the genetic variation for several traits, up until 60 weeks.

For example, in 1960 laying hens averaged 230 eggs per cycle, yielding 5,000 eggs per ton of feed. Today’s commercial flocks average 430 eggs per cycle and yield a staggering 9,500 eggs per ton of feed, with free range flocks of Dekalb White birds regularly achieving 500 eggs per hen housed over 100-week cycles.

A dramatic drop in chick placements

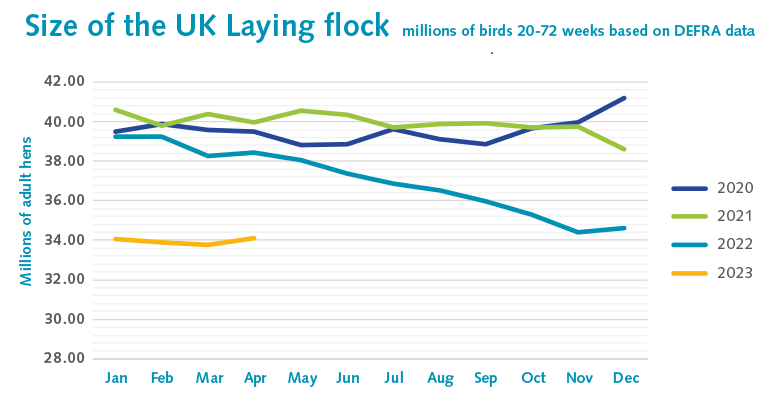

Yet despite this extraordinary achievement the industry is currently unable to fulfil the demand for its products. Eggs have fallen into shortage this autumn to the point where some retailers have been stocking European eggs not produced to the higher standards required by UK codes of practice such as the Lion Code. This shortage has been driven by a dramatic drop in chick placements from 41m to 34m. At first, this was primarily colony production but in recent months the drop has also moved to free range.

The press has ascribed the current situation to avian influenza but whilst this is a factor, market dynamics are much more complex than flocks being culled due to AI. After all, more hens were culled in the previous AI season. Consumption patterns during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, free-range expansion, production risk and cost, planning consent difficulties and build costs, have all played a role.

Since the rolling sequence of announcements from one retailer after another placing a deadline of 2025 to sell only non-colony cage eggs, the industry has been attempting to gear up for this new future. Primarily this has been through expansion in free-range with capacity growing from 26 to 29m during the period of 2019-2021. Falling levels of egg sales at retail level, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 lockdown, combined with this expansion generated a free-range surplus that put pressure on egg prices. The poor market seen in 2021, particularly in the summer, left some egg supply contracts exposed to weak margins. Feed prices were expected to fall at the end of 2021, but instead they steadily increased, and then came Putin’s treacherous invasion of Ukraine. Feed and energy price surges piled onto already increasing costs driven by a supply chain in recovery from the pandemic. Labour shortages worsened by our departure from the single market, and feed prices already at historically high levels, added to the pressures.

Rapidly rising costs and poor egg prices

Against this background of rapidly rising costs and poor egg prices, producers faced the huge production risks of Avian Influenza which insurance companies were increasingly unwilling to underwrite. Free range expansion had already stalled against weak prices and increasing costs at the end of 2021 but in 2022 we saw an increasing proportion of producers delaying or deciding not to re-stock free-range production units. Retailers were clearly warned of the effects of this in early spring but paid no heed. Buyers clearly did not realise the inelasticity of the supply chain nor the time it takes to turn on supply again. This position has been compounded by reduced placings in the EU due to similar dynamics and the huge cost added to supply chains in France, Germany, and the Benelux by recent bans on the culling of male chicks.

Of course, neither the egg industry nor retailers wish to risk significant falls in egg sales by shocking consumers with price increases but there is insufficient margin for the sector to absorb the price shocks we have seen in the last twelve months, especially with the margin pressures already seen in 2021. Fundamentally it is about a consistent and sustainable margin that allows the confidence to invest and improve poultry businesses. Many of the new entrants, encouraged into free range egg production by the demands of retailers for cage-free eggs, are small family farms who borrowed against their inheritances. The intransigence of retailers to reflect cost increases in prices has placed undue stress on hard working farming families who fear losing farms that have been with them for generations.

The egg industry needs to manage the production levels correctly to meet demand and avoid market weakening levels of surplus. How many birds to we need? What system of production?

- Ideally, the UK would be self-sufficient for eggs so that food service and manufacturing sectors could benefit from an egg supply with the highest levels of health status, controlled antibiotic use, and animal welfare. However, what is the realistic size of the UK flock that will provide sufficient cover for UK egg demand including seasonal peaks. Yearly placements of 34m are too low and 41m was too high. Extended cycles also need to be factored in as we move to more white egg production.

- What is the future of colony cage? Given the cost-of-living crisis and the stalling of free-range capacity growth, will some retailers quietly extend the shelf life of this production system? It does have advantages in production cost, carbon footprint and disease control (particularly AI). How much colony egg can we sell to food service and manufacturing, and can we drive better loyalty to UK/Lion egg in these sectors?

- Will retailers give sufficient guarantees and return on investment to drive more significant levels of barn egg production? Conversion from colony to barn is expensive and not without challenges. In the run up to the ban of traditional cages in 2012, packers and producers were assured that colony would be supported and yet by 2016, retailers had announced their intention to stop selling colony egg. Will this be the same for barn eggs?

- How many free-range birds in production are needed? Free-range capacity is already at 29m or 66% of UK production capacity. It is also the dominant production type of eggs sold at retail, which in turn accounts for 65% of UK egg consumption, so is this already enough capacity? Probably not as there is a need for surplus capacity to meet peak demand and supply food service and manufacture. How many hens is this and will egg buyers pay enough to cover surplus for retail peak demand and higher welfare eggs in non-retail?

A beacon of hope

One beacon of hope for the egg sector is the growing acceptance of white eggs by consumers, and the increasing numbers of producers declaring their admiration for the performance of white birds. The indications are that the UK will soon follow the path of the Dutch market, which was 60% brown /40% white in 2012 and moved to 35% brown/65% white by 2019. Their market is still moving towards white eggs today, with the German market following the same trajectory. Longer term, increased pressure for ending beak treatment will also speed the transition to white egg breeds.

Combining excellent liveability, extended production cycles, superb persistency and ease of management with an excellent feed conversion ratio, the Dekalb White consistently produces high numbers of first quality eggs, per hen housed. With the potential to keep the flocks in production for up to 100 weeks, 3 flocks are managed in the same time as 4 brown flocks, which translates directly into savings on pullets, transport, restocking and turnaround, with consequent lowering of carbon footprint and improved welfare.

A study on the ecological footprint of white versus brown egg layers by Mollenhurst & Haas in 2019 found 2179g of CO2 equivalent for every kg of egg for brown egg layers, compared to 2093g for white flocks. By 2030, this is expected to improve to 1975g for brown and 1851g for white. The differences are predominately due to the extension of layer cycles.

For the last few years, producers lucky enough to have negotiated contracts for white eggs, and brave enough to order white flocks, have been almost evangelical about the combination of flock management and financial advantages their white birds deliver. Almost without exception, they have declared their intention to reorder white birds.

Flock after flock of Dekalb White layers are achieving the magic 500 eggs per cycle, recording excellent feed conversion, low mortality, excellent feathering, and generally demonstrating the ease of management that so endears them to producers. In addition, consumer resistance to white eggs is dropping away, retailers are now actively stocking white eggs, and there are signs that the white revolution is here. So much so that in a highly challenging market, white bird placings are rising month on month.

Joice and Hill are the UK distributor of Hendrix Genetics’ portfolio of layer breeds, including the ‘world’s most productive layer’, the Dekalb White, and the world class brown layers, Bovans, ISA, Shaver and Warren. From their modern hatchery in Peterborough, they hatch over 12-million-day old chicks per year, which equates to an approximate market share of 35%. Hatching eggs are supplied from their own brown and white parent stock farms, located in the UK.